Global Affairs #12:

Strangers on a Train: an anecdote.

by Ted

The moonlit scene passing outside the carriage window was from a postcard. It was all still, and bright, and snow-covered woods, perfect for a Christmas card. It was below freezing out there. Inside the railway carriage, there was something wrong with the heating system. It was well into the 80s Fahrenheit. I really didn't need that much heat. I was already sweating profusely and running a fever. I had an attack of pleurisy, originally a cold I had not looked after, then it got into my chest. If I wasn't careful, I would end up with pneumonia.

The train was somewhere in southern Austria, approaching Germany. I had been on the train for two full days already having left from Athens. There were not a lot of other passengers on this train. I had had the compartment to myself for much of the journey, which was fine, because my coughing was not keeping others awake, and also because it was not a sleeper car, and I could stretch out on the empty seats.

I complained to the porter in mostly sign language about the heat, and from his broken English I understood that they knew of the problem and would try to do something about it at the next stop. As it was an express train, stopping rarely, that didn't help much. I continued to sweat - and cough.

The next stop happened to be at the border into Germany at about one in the morning. The few of us on that particular car were order out, with our luggage, onto the station platform of some forlorn little German village. There was no waiting room open, or any other shelter other than the platform roof, and the closed ticket office and customs. What customs checking there was had been done on the train before we arrived.

We stood out there in the cold for perhaps forty minutes while they uncoupled our car, shunted it away to a siding, and replaced it with another. Just as well I had lugged a heavy duffle coat across Europe with me.

Finally we were allowed back on, and the porter guided us to our new compartments.

When I entered my new one, I found I was no longer alone. I don't know whether the gentleman who was now seated opposite me had embarked at this station, of whether he had already been on board, in another compartment from me.

As I stowed my luggage on the overhead rack, I sized him up. He was a handsome, distinguished-looking man, somewhere between 50 and 55, about twice my age at the time.. He had silvery grey hair and a rugged face. There was also a cane on the seat beside him. I gathered he must be lame in one leg.

When he greeted me with "guten Abend" I knew that he was German.

I replied with "guten Abend" but added "Mein Deutsch ist schlecht." (My German is poor.)

"Ah! An Englisher?" he asked

"nein - eine kanadische. (No. A Canadian)" I informed him.

"But not a Quebecois, I think," he smiled, "so we will speak in English. I am quite fluent with that language.

My pleurisy subjected me to another bout of coughing after the effort of stowing my luggage. I didn't yet remove my duffle coat, because this new carriage had been sitting unheated at a siding for quite a while. While the other had been overheated, this one was freezing, although some heat was beginning to seep in from the radiators. The train was moving once more and the snowscape slipped by outside.

"You are not well," the man observed. "Perhaps you should get a sleeper car."

"This will be fine as long as I have the whole seat to myself," I pointed out. "There are blankets in the rack."

Where are you going?" he asked.

"Munich, then Calais," I told him. "I have a ship to catch from Southampton in four days."

"You will be cutting things fine," he commented.

"And where are you headed?" I asked.

"To München," he told me.

"Is that where you're from?" I asked.

"It was, once upon a time," he said, rather sadly. "I was stationed there during the war."

"World War Two?"

"Of course," he laughed. "I am not old enough for World War One!"

To be honest, I didn't think he looked old enough to be in World War Two, either. and told him so.

"I was very young," he replied. "I was only twenty when it ended. I was in a Russian prison camp for two years after that."

A little quick math told me that the man was even younger that I took him to be.

I nodded to his cane.

"is that from a war wound?" I asked.

"No," he laughed. "I got drunk and fell off a bar stool a couple of years ago. I fractured my ankle badly."

"Did you see much action during the war?" I asked.

"Much action!" he observed, "especially during the final year."

"What did you do in the war?" I asked.

"I was a fighter pilot," he told me. "I was a Hauptmann in the Luftwaffe,"

"Hauptmann?" I asked.

"Hmm," he pondered. "I think you might say lieutenant, or maybe flight lieutenant. I flew a Messerschmitt."

"You shot down our bombers?" I accused, rather inanely.

"They were bombing our cities," he shrugged.

"Were you in the Nazi Party?"

"All officers who wanted to get ahead joined the Nazi Party, whether we believed their politics or not," he countered.

"What do you think of Hitler?" I asked.

"He was a great leader," he responded. "Ultimately a madman, but a great leader, all the same."

My hackles rose. Here was this man defending the most evil man of the century. How dare he!

"What about his treatment of the Jews? And the homosexuals?" I asked. I didn't add that I was both. My feeble German came from my Jewish-German grandparents, refugees from Hitler's Germany. My homosexuality was all my own.

"I agree. That was bad," he pondered.

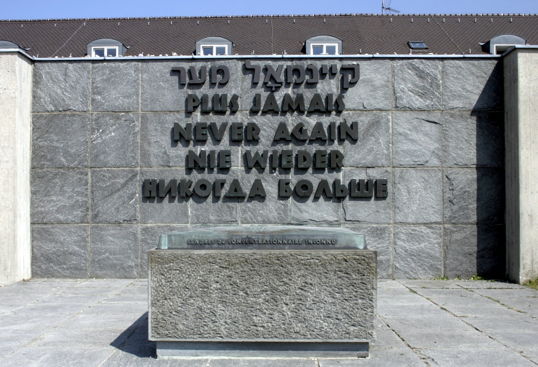

"You said you lived in Munich," I persisted. "Surely you knew what was going on at Dachau?"

My own memories of a recent visit to the site of the Dachau concentration camp flooded back. I went with two American girls I had met. After we had gone through the museum, and we had watched the short documentary film (at which there were paramedics on site for those who fainted or got sick), the girls and I could hardly speak, so horrified and affected were we.

I remember we came across an Italian family, laughing and joking, and having a picnic lunch and sitting on the tomb of the ashes of the unknown concentration camp prisoner, in front of the memorial wall , which reads in five languages: Never Again.

The three of us went crazy at this family, who could not understand why we were so irate. It almost came to blows.

"I knew nothing about Dachau," he insisted.

"That's just what the people who lived in the village right outside the gates claimed, too," I sneered.

"I swear," he protested. "We knew Jews were being forced into camps, but we never knew what was happening there.

"Ha!" I sneered, disbelieving him.

Outside, the night was clean and white and serene, the moonlit snow-covered woods flashing by. Inside, the tension was high.

"Through our business connections, my family helped many of our Jewish friends to escape Germany into France and Switzerland," he claimed.

"But you did nothing to stop the camps!" I accused.

"What could one young man do?" he asked. "To oppose the Führer would have been have been suicide — insane."

"So you did nothing. You are just as guilty as he is," I claimed, in my self-righteous immaturity.

Der Hauptmann went silent. We sat in the carriage, not speaking, while I seethed in impotent fury against the German machine, twenty-five years after the war and its atrocities.

I sneaked a glance at the handsome older man opposite me. I saw tears trickling down his cheek. Were they from guilt, or remorse, or sorrow for those victims of the war? I didn't ask, and he wiped them away with a handkerchief and regained his composure.

Another bout of coughing overtook me. I felt like my lungs were being ripped out. There was blood in the phlegm I coughed up.

The German stood and reached down his valise from the overhead rack. He opened it, searched round inside, then handed me a bottle which was obviously cough medicine.

"Take it," he insisted. "It will soothe the cough and ease the pain. It has codeine - and quite a bit of alcohol," he smiled.

Reluctant to be beholden to him, I took it never-the-less. I took a mighty swig. The soothing effects took place almost immediately.

"Keep it," he insisted. "It would not be good for you to catch your ship too sick to enjoy." He smiled.

As I sat, being lulled by the clickety-clack of the rails beneath us and the pleasant warmth from the radiator which had by now filled the compartment, I contemplated this man again. I began to feel guilt for being so accusative, so judgmental. After all, he had been younger than I was now when the war ended. And he had been kind to me. And I had made him cry! I felt like a jerk.

I was starting to doze off, and decided to do it more comfortably. I stripped off to my underpants and stretched out on the whole seat, across from the Hauptmann. It was too warm now for the railway blanket, so I just put it under my head as a pillow. But my guilt at loading the Der Hauptmann with guilt kept running through my mind like the clickety-clack of the wheels on the rails.

Clickety-clack, Clickety-clack, Clickety-clack, Clickety-clack …

I woke with a start, not sure at first where i was. The room was dimly lit. I realized it was the railway compartment. The blinds over the corridor windows had been drawn, and the compartment light dimmed.

Der Hauptmann was sitting between my spread legs, stark naked! I didn't move or say anything.

The man took my lack of reaction as a tacit agreement to what was happening.

"You don't mind, I hope," he smiled. "I saw the bulge in your underpants, and I just couldn't resist. I gather you were having a — what do you call it? — a wet dream?

It was partially true. I had been having some sort of erotic dream, but it wasn't wet - yet!

He reached forward and drew the front of my jockeys down over my cock, which popped up, freed of restraint.

"Ah, very nice," he said. "You are circumcised. Are you Jewish?" he asked.

"My grandparents were," I said. "So I guess I am, too. I am not a religious person."

I could see a nice, thick, uncut cock nestled between his legs. He saw me staring at it.

"And are you a homosexual, too?" he asked. "Like me?"

"Yes," I admitted.

"So you might now better understand why I never questioned the Nazi party. I could so easily have ended up in the concentration camps myself."

"I see," I replied.

He reached forward and grasped my penis. I didn't react. I let him masturbate me slowly, while he edged my underpants down further. I helped him out there by lifting my buttocks so he could slide then down my legs, then lifted one leg to get partly out of them altogether.

"May I suck it?" he asked.

"Yes," I nodded.

He leaned forward, licked away the drop of pre-cum hanging on the end, then took my cock into his mouth

The German fighter pilot then proceeded to give me one of the greatest blow-jobs I have ever had, even to this day, decades later. I was in danger of falling off the narrow seat, so I sat up to give him better access, and to help myself to breathe a little easier.

When I had blown my load into his mouth and he had swallowed my cum hungrily, he didn't stop, but kept on sucking and gnawing at my now-tender knob, until I began to swell once more. The he really went to work on it, using tongue and teeth and lips, sucking and licking, chewing, and sliding his teeth and tongue over the most sensitive spots on my cock.

Within a few minutes I was again spurting cum into the man's mouth, and he was once more drinking it down.

If I had let him, I'm sure he would have done it a third time, but I was exhausted from the orgasms and the pleurisy. I pushed his head away, pulled up my underwear from where it dangled round one ankle, and lay back on my side on the narrow carriage seat. I curled into the fetal position as best I could and closed my eyes.

I heard Der Hauptmann sigh, then go back to his own seat. The rustling I heard as I drifted off to sleep once more I presumed was the man dressing himself.

When I woke again, it was morning. No longer were there woods flashing by outside, but some grey industrial city. I was alone in the carriage. Der Hauptmann was gone, and so were his valise and cane. I don't know where he had gone. I don't think the train had stopped anywhere, but it may have.

All that remained to mark his passing was a note in beautiful handwriting. It was on the little drop-down table under the carriage window, along with an orange, a banana, and a bar of chocolate.

The note read:

Mein junger Freund:

I hope some day you will find it in your heart to forgive me. I was young - like you are now. I was patriotic - as I'm sure you are from the flag on your jacket.

We all make mistakes we regret in life, but they can rarely be fixed.

May your journey be free of such regrets.

Your friend

Karl Schulman

(Der Hauptmann)

If you enjoyed my story (or if you didn't), please add your comments below: